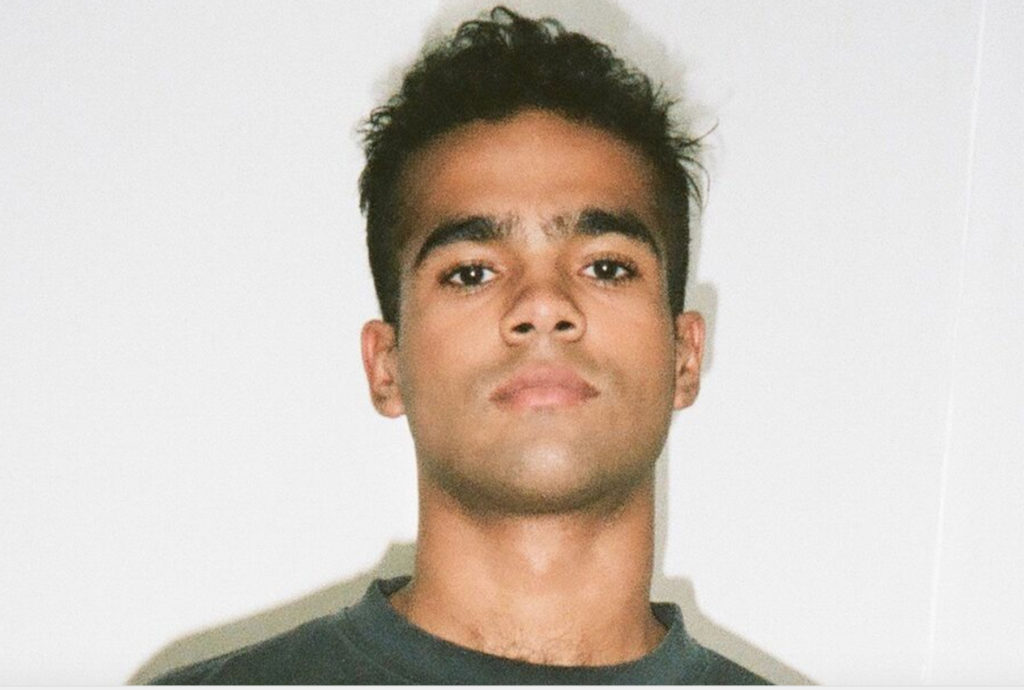

It’s not uncommon for filmmakers to start making movies as teenagers, taking the trusty (depending on the era) 8mm camera/VHS camcorder/mini-DV/iPhone and shooting scenes with friends. It’s much less common, however, to complete an award-winning SAG-AFTRA signatory feature film starring a Spirit Award-nominated actor, while you are still in high school. But that’s the story of PHILLIP YOUMANS and his feature debut as director, screenwriter, producer, cinematographer, and editor, BURNING CANE.

Hailing from the seventh ward of New Orleans, Youmans fell in love with filmmaking and acting at a young age (yes, even younger than he is now). As a junior at the New Orleans Center for Creative Arts (NOCCA), Phillip began work on Burning Cane, centered on a woman (Karen Kaia Livers), her son (Dominique McClellan), and her pastor (Wendell Pierce) in a religious community in rural Louisiana. Beasts of the Southern Wild director Benh Zeitlin eventually signed on as Executive Producer and Youmans unveiled the finished film at the 2019 Tribeca Film Festival. He left Tribeca a record-breaker, becoming the youngest filmmaker (at age 19) to win the festival’s Best Narrative Feature Award, as well as the first African-American director to ever win the prize; Youmans also won Best Cinematography and Pierce was named Best Actor. Since then, Youmans was nominated for a Gotham Award for Breakthrough Director.

It’s all evidence that the industry is taking the young director very seriously. In addition to Zeitlin’s involvement with the film, another major filmmaker took interest as Ava DuVernay (Selma) and her company ARRAY picked up distribution rights, with a theatrical run in select theaters (including Los Angeles) on November 8.

We were lucky enough to chat with writer/director/editor/DP Phillip Youmans about making Burning Cane, working with top talent, and achieving so much at such a young age.

——

COLIN McCORMACK: Congrats on everything. You have the Gotham Award nomination, the film’s coming out. From the outside, it seems like a sudden rush of success, but living in it, does it feel like it’s been a long slog to get here?

PHILLIP YOUMANS: That’s a good question, man. I feel like I’ve definitely put in the work up to this point, but I could have never expected it would work out this well. You put the work in and it’s sometimes not as easy to remind myself about how awesome things have panned out. Because it feels like this kinetic clock just constantly moving, moving, moving, whether it’s editing here or doing a piece of writing here or emailing– because emailing is like half the job. I’m really reminded of it from an outside perspective whenever someone will ask me about the whole process, then it’ll hit me. I’ll be hit with all the crazy memories that came around Tribeca, where I saw and met people I thought I would never meet. I feel nothing but fortunate that things have worked out this well. I never could have anticipated that they’d work out this well, but I’ve been really putting my everything into this for as long as I can remember.

CM: I know you’re in the middle of the promotional period of the film, but are you in school? Are you currently making films? I assume you’re keeping busy because you seem like that type of productive person.

PY: I am technically still enrolled at NYU, but I’m taking a semester off. I’m very clear that I want to make more movies. I have nothing but respect for NYU and everyone over there, but I have to be honest about what I want for my career and what I want for myself without really thinking about how others will feel about it or how my family will feel about it. I have to be more honest with myself in the whole conversation because there’s still a lot more learning that I can do. I can still make work and get better, but to have the opportunity to be able to do that within the industry and to work and make a living at this, is an opportunity that I can’t pass up. I feel like I’d regret not going full-throttle into that situation, as opposed to trying to work a lot of those things out and experiment while still in class. It’s an exciting, busy time, I’d say. I’m technically a sophomore right now, just making movies and music videos. This is what I love doing, so this is it for me.

CM: Going back a little way, you were a pretty young kid when your home state of Louisiana was probably the biggest film production hub in the United States. Were you able to experience any of that or see that as a resident growing up there?

PY: Everybody back in New Orleans calls it “Hollywood South,” because there’s so much production work that comes in. But it’s interesting because really a lot of those are [outside studio productions]… By the time they were coming to New Orleans, they were casting basically all the smaller roles. All of the main key roles and a lot of the crew and main key creatives were coming from outside the city at the time. So I think it’s interesting looking at how much production work was coming in, but in terms of art that was created and had its inception in New Orleans, that’s something that’s still developing.

I was PA’ing and getting onto any production I could get onto in high school and there was definitely no shortage of productions in the city; pretty much every weekend. So I felt that in terms of getting applicable on-set experience. But in terms of it feeling like it could be a hotbed as a creator to get your project out into the world, I don’t think it felt like that. It’s something that I’ve become more aware of now, because I thought I always had to be in New York or L.A. to make a move, but when I fell back onto my instincts and my roots and onto stuff I actually knew, in a world I knew, an ecosystem I was familiar with, then all of that opened up.

CM: Your high school seems like it was a pretty unique place for someone with artistic aspirations. Did you know before you started attending the experience you’d be able to get there?

PY: It was the only high school institution around the country that had a full-fledged film and media program. And there were other people within my Media Arts Department that weren’t only doing film, they were doing audio production or they were in rock bands and they wanted to have a soundstage and studio space to do it, so it wasn’t just for dedicated film students… The department was spearheaded by a guy named Isaac Webb, who came from Idyllwild Arts and came to the Media Arts program in New Orleans and really revamped it, stocked us up with new cameras, new gear, all that kind of stuff. So by the time I came there, it really had the same applicable production usage of any top-flight film school that I’ve ever visited or seen.

CM: While you were there is when you conceived of Burning Cane as a short film, correct?

PY: Yep.

CM: Was the short script completed before you decided to expand it?

PY: Yes. Moving into production, I was going to shoot that short but then I actually made another short that was actually really bad [laughs]. And throughout that time, I was having conversations with Isaac Webb and he was telling me how he thought [Burning Cane] could be a feature, so we had a meeting about that. I was developing in tandem with me making this other short, and the other short didn’t really have my full attention, which I recognize now in retrospect. With the short to the feature, I expanded the community, expanded Daniel and Helen’s dynamic. Initially [in the short], we live with and meet Helen, then Daniel comes in unexpectedly. They’re estranged, so Helen is reckoning with who she believes her son has become and reckoning with the guilt she feels as a mother for how it turned out. And that same dynamic is present in Burning Cane toward the end of the film, but I wanted to expand it in upping Daniel and his son Jeremiah and their isolation in a mind-numbing way.

The first draft of the script was very different than how the film stands today because at the midway point, that’s when Daniel goes to Laurel Valley and that’s when we first see Helen. The problem with that that I wasn’t aware of until the beginning of post was when people were viewing the film – and this is why feedback is so valuable – there was no way to directly associate or know that Helen was Daniel’s mother. And without that realization, so much of the first half of the film loses its weight without us being able to connect the dots about who these people are and what they mean to each other. That was something we became aware of in post, so I sort of re-engineered part of the edit with that in mind and we moved into production with Wendell’s role at the top expanded and bisecting with Daniel and Helen.

CM: In terms of getting feedback, from the first draft of the script throughout watching the first cut of the film, who was part of your circle of trusted people that you’d ask for notes or feedback?

PY: For feedback, I would go to pretty much everybody within my team and send them the new drafts of the script. So it started with Isaac Webb, then it was my producers and friends Mose Mayer and Ojo Akinlana. Karen Kaia Livers was the first casting piece that we brought in; she was Helen, our lead character, and she was also a vocal respondent for some of the feedback in those first initial drafts. But I kept it intimate in that way, everyone who was in the team that was going to be moving forward with us – my main producers, Webb, and Kaia. My mother also, I’d say. It’s interesting with her feedback in that it’s not always unbiased and she couldn’t always be objective, but I do still respect her creative opinion, so I did share drafts of the script with her and I did take some of her notes as well if they were valid to the story. And some of my friends in casting, I would have them read it and give me feedback. But mostly it was concentrated on my core team that I moved forward with into production.

CM: Karen Kaia Livers seems like one of those people that really helped push the film forward in a significant way. Not only is she a casting director [and producer], but she ended up playing one of your lead roles. Could you explain how the connection to her came about?

PY: Webb reached out to Kaia because he wanted a local casting director. This is when I was at NOCCA. Webb and Kaia knew each other because Kaia worked on Webb’s first feature, a film called First Born, and then Kaia was I think the line producer on Treme, the HBO series that shot in New Orleans. So he brought her in because he thought she could help me – since this was my biggest production-level situation – plan out everything and move everything forward logistically. But when Kaia read the script, she said that she wanted to play Helen. So I read with her and it was clear that was a no-brainer decision. From that point on, Kaia was a part of the team, helping logistically as a producer and being a core [collaborator] through the end.

CM: It’s also a pretty wild story of how you ended up getting connected to Wendell Pierce. A customer you were waiting on at your restaurant job happened to be friends with him?

PY: Yeah, I was waiting on a woman named Lula Elzy at Morning Call, the beignet stand where I was working. I got a high school job initially, in truth, because I was in a car accident and my insurance rates went up and my mother told me I had to get a job [laughs]. So I went to Morning Call and was working there for the month leading up to the film, I think it was December or November 2016. Once the film was my focus, I started picking up extra shifts, working after school and weekends, just trying to stock up cash. Beignets aren’t that expensive, but when people are buying them quickly and in bulk, the customers come in and out and the tour buses come in and you know how the tourists are [laughs]. So I made enough there to put gas in my car, maybe go on dates sometimes, but also stock up cash for production. While I was there, I met Lula, who texted Wendell after we had been talking about my film. And I got his email from that and he said, “Send me the script.” So I sent it, then told him, “Don’t read it.” And I went back, took a week and I expanded the pastor’s role as more than just a vessel that we view Helen through and more as a centerpiece in the film. Fleshing out the role of the pastor solidified the commentary I wanted to make in the film, and I think Wendell definitely motivated that.

CM: With so many micro-budget films, landing even one recognizable actor can mean all the difference in terms of its commercial viability. It sounds like you didn’t have a plan from the get-go to go after bigger name talent, but did you ever have that as a pipe dream before the Wendell connection came about?

PY: We were all aware that Wendell coming on sort of upped the ante of it, but I didn’t want to get hung up on the idea that it confirmed anything, that it confirmed that eyes would ever see it. But I did feel like it upped the ante in an incredible way for us. It matured us in that we had to be especially accountable for everything that happened on set because we had limited time with [Wendell] and everything needed to run as smoothly as possible. And I think that course of action ran through the rest of production. Before Wendell, I had an IMDb Pro account at the time so I thought, Why don’t I reach out to Morgan Freeman? Let me try that, blah blah blah. I’m pretty sure I called but never heard anything back.

Though I have to say, in terms of reaching out to name talent, I was fortunate that Wendell’s an amazing actor and I was able to get in touch with him directly and not have to go through his representation. Representation is there for protection, to be a sort of wall. And since we had no real resources, I had no real track record, there was no way I was ever going to get in touch with any of these people directly as much as I tried to. So getting in touch with Wendell directly – having Lula there – was such a fortunate situation. Wendell is established and is a name because of how talented he is. He is honestly a student of the craft, through and through, and I am mad blessed in a non-religious way that Wendell even wanted to be a part of the project. It was a validating thing, you know? That an actor of his stature, with that much power and sway within the community, wanted to be a part of my film just made me feel better and more confident about it as a whole.

CM: Being in a position of authority [as director] at such a young age, what was that like when you’re overseeing department heads that could be so much older? Was it always comfortable, or did you have to find your footing along the way?

PY: For me, it was a little different. The biggest age differences came with my actors. In terms of crew, it was pretty much all filled out with people my age, outside of some of our producers. The people really grinding on set with me day-to-day were my best friends. I also knew they were there donating their time. There was never going to be any hostility, any talking down, any hierarchy that I would have ever enforced. For one, I don’t like sets moving that way. I hate there being any hostility whatsoever because it takes so much of the fun out of it. We’re making art, it’s the best thing in the world. For us, there was never any attitude, especially from me knowing that I was paying people either nothing or well below industry rates, given the resources that we had. There was never any moment where I felt I needed to impose or enforce any sort of hierarchy. I’d never want to do that anyway, but especially in the case of Burning Cane. There are too many people who are there because they wanted to be there, and me being anything less than completely human and vulnerable and speaking to them with respect, anything less than that would have been intolerable. I’ve never looked at directing as a power trip. I feel really awesome that I get to be a driving creative force behind these projects, but I’ve never viewed it and never will view it as a power trip. That’s not what it’s about at all.

CM: Did you and the crew live together during some of the filming?

PY: Yeah, we stayed in an Airbnb together, cast and crew. All of us in this single-family home in Houma.

CM: So was there a feeling that this was something special and it wasn’t just a typical clock-in/clock-out job? There was a little more investment on everyone’s part.

PY: Oh yeah, we were a family, for sure. It was such a family and friendly kind of atmosphere. It really felt like we were all hanging out, having a blast, making good art. Even though we had time constraints and our resources were low, none of that ever felt like it was going to stop us from getting anything done. We really felt like a family. We didn’t have the luxury of being able to put everybody in separate hotel rooms, so there was definitely stacking in terms of two or three people in the same bedroom. Me and Mose and Ojo working on call sheets in the same bed, by the time we’d fall asleep, wake up at 6am and we gotta be on set at 6:30. Stuff like that, you know what I’m saying?

CM: What was shooting schedule like?

PY: We started shooting July 17. We shot 17 days of principal and 21 days of pickups. All of Wendell’s shooting was done over the course of two full days, like two 14- or 16-hour days.

CM: Wow, that’s insane.

PY: [Laughs] It was insane. Me and Wendell laughed about how he wasn’t really used to a production that was moving that quickly. I’d do one or two takes and he’d be like, “Really? That’s it?” He actually had to tell me, “Phil, get some more coverage.” [Laughs] It was kinetic, it happened fast, we had very little time and very little money, and also school was starting in August. So we needed to get as much of production done before school started for it to feel like it was really going to be seen through fruition. Because breaking it up to weekends for principal didn’t seem sustainable. For pickups, [weekends] were okay, but for the bulk of principal photography, no.

CM: ARRAY picked the film up, which isn’t your everyday kind of hands-off distribution company. What’s the experience been like working with them?

PY: They’re amazing. They have such an honorable mission as a distributor. They’re literally dedicated to promoting the work of filmmakers of color and women of all kinds, that’s the mission statement and it’s incredibly true. ARRAY is so dope too because it’s a company founded and almost completely staffed with brilliant black women. And Burning Cane is an unapologetically Southern black story. It was such a grassroots production and ARRAY is such a grassroots distributor, it feels like a match made in heaven. I can’t lie, I feel mad fortunate for that too.

__

Thank you to Phillip Youmans for talking with us about BURNING CANE. Learn more about the film at the ARRAY website or follow the film on Twitter, Facebook, or Instagram.

This interview has been edited and condensed for clarity.

If you’re an independent filmmaker or know of an independent film-related topic we should write about, email blogadmin@sagindie.org for consideration.