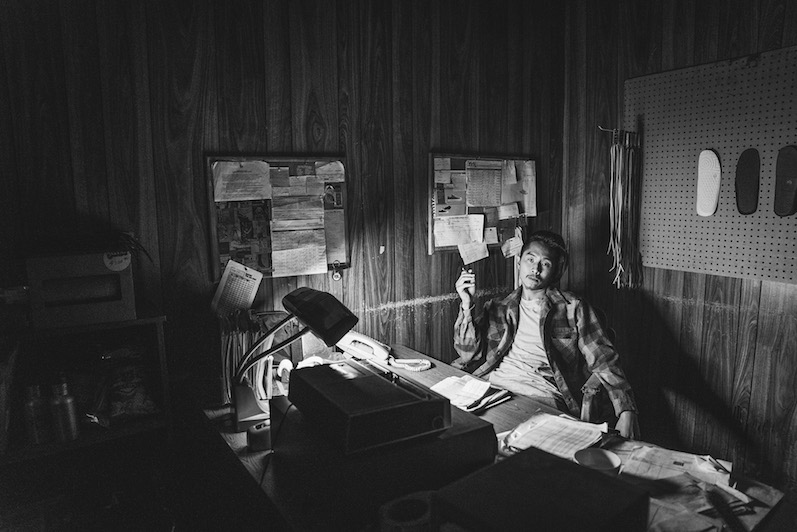

JUSTIN CHON wrote, directed, and stars in GOOK, a coming-of-age drama taking place on the day leading to the 1992 Los Angeles riots. Chon and David So play Korean-American brothers trying to keep their family-owned shoe store afloat. As racial tensions in the city give way to the Rodney King verdict and the uprising that followed, the film’s brothers – along with a young African-American girl from the neighborhood (Simone Baker) – must keep themselves safe in the midst of encroaching violence and upheaval.

Gook marks the second feature directorial effort for Chon, an actor known for the massively popular Twilight franchise, the films 21 & Over and Seoul Searching, and the TV series Dr. Ken. As a filmmaker, Chon wrote and directed a number of shorts before making his feature debut in 2015 with Man Up, in which he also starred. His latest, Gook, won an Audience Award at the 2017 Sundance Film Festival, and will hit theaters via Samuel Goldwyn Films on August 18.

Justin Chon took some time to speak with us about making such a personal film as Gook, and his path from actor to filmmaker.

——

COLIN McCORMACK: The film is partially based on your family’s experience in the aftermath of the Rodney King verdict. When did you start thinking of it as a potential movie idea?

JUSTIN CHON: About five or six years ago. I had auditioned for a few LA riot [themed] films over the years. These days we talk about the difference between diversity and representation; diversity is more like we’re there but doesn’t necessarily mean it actually represents us, and I think representation means it’s based on a reality or truth. In some of the [projects, Korean-Americans] are in it; we’re just included in the conversation because we were there, rather than actually going into depth about our sort of plight. All those other stories are amazing and they should be told, but when the story ends up being told as more of a Black and White situation, I think it’s imperative that there are other perspectives as well. Korean businesses being the hardest financially hit during the riots, it only makes sense that a film from a Korean-American perspective should be made.

CM: What was the location scouting process like for you? Were you filming in and visiting areas and businesses that had actually been affected by the riots?

JC: Not necessarily, because when you’re making a film there are so many logistical considerations that need to be made. First of all, we had an 11-year-old [actress] and half our film is at night, so we had to make sure wherever we were going to shoot was going to be safe. But we did [film] in the relative vicinity. We shot in Gardena, between Compton and Inglewood. That area was affected, it was hit, it just wasn’t the epicenter. We shot some stuff– Kamilla’s house was actually in South Central. When Daniel is walking around the streets, that’s South Central. But the store itself was in Gardena.

CM: Speaking of logistical considerations, when it comes to cost and logistics for a period piece – since the film takes place in 1992 – was that a big concern or something you had to keep in mind in terms of avoiding showing modern cars or [anachronistic] things in the background?

JC: Yeah, [we did] as much as we were humanly able to do. Obviously, our film is indie and we don’t have the high budgets to close down streets and dress them with period-perfect cars. But location-wise, it was really important that that building was standalone. Because if I’m going to burn down – that was CG – but if I’m going to burn down the building in the film, morally would you be burning down other businesses that are connected? So it needed to be a standalone building; that was a huge consideration when I was location scouting. As you saw in the film, it’s just kind of on its own, so logistic-wise it made it a little bit easier. But that street that’s in front of the store, that’s a very very busy street so we had a lot of sound issues and shooting that direction was pretty hard.

CM: Characters watch a lot of the real-life news coverage of the trial and the riots. Was researching and licensing that news footage a lengthy process?

JC: Yeah, I went through a lot of footage. Funny enough, I even found footage of John Singleton leaving the trial at the courthouse and his reaction. I was contemplating whether I should use that, but it was just too meta. It takes you out of it if you see a filmmaker in news footage in the film; it’s just too gnarly. I went through tons and tons of footage, at least the footage I had access to. There are some really amazing documentaries about the riots that came out this year, like LA 92 or Burn Motherfucker Burn. John Singleton had one, I think it was called LA Burning. Those have much more comprehensive footage because it’s documentary. Mine being more of a narrative, I just was trying to look for footage of important moments in the day. But it’s playing in the background so it becomes a part of the day.

CM: Switching to your cast for a little bit, your dad plays [liquor store owner] Mr. Kim in the film. He was a famous child actor in South Korea, correct?

JC: Yes.

CM: Did you get feedback from him as how you held up as a co-star and a director?

JC: [Laughs] Yeah, he’s always not impressed with what I do. It was really hard to get him to do the film in the first place. But once he got on set, he was an actor. He asked the right questions, he was collaborative, he took directions very well. So during that 12-hour period when we’d shoot he’d be the real deal. And then as soon as we’d wrap, he’s lecturing me about stupid bullshit that has nothing to do with the film.

CM: And he came to Sundance when you premiered it?

JC: He did, actually. He was really being grumpy, saying, “Don’t even think about calling me to the stage.” He said he was going to wear hiking gear so I’d be embarrassed if I called him to the stage. But he was the first one on-stage and gave a little speech monologue and I think enjoyed himself. But even at the after-party, he sort of lectured me on having too many drinks and that I need to be responsible and take the interviews seriously and all that.

CM: Does he officially have the acting bug again? Does he want you to write him another starring role?

JC: No, no. It’s been tough for me to get him to even come to any of the screenings. I tricked him once for an LA Times interview; he thought it was just going to be pictures but when he came and they wanted him to talk, to the end he wouldn’t do the interview. I had to do the interview by myself. No, he wants no part of it. This was his final gift in life to me. He said, “Don’t even ask me for five bucks ever again.”

CM: How did you find Simone Baker?

JC: I auditioned some traditional child actors and they were very polished. I was looking for somebody that felt like they were real and not rehearsed. So after I auditioned some, I started asking around and we called some African-American churches and then someone suggested the Fernando Pullum Art Center in Leimert Park. It’s a community center [that] subsists on donations and fundraising, and that’s where we found Simone.

CM: When you’re directing a child actor, do you alter your directing style at all or do you come at it as you are with all your other actors?

JC: I’m not easier with her, but I do spend a lot more time. It takes more time to explain and help them understand what the situation is. Child actors are so resilient and so intuitive that once they get it, they get it. They’re not asking any questions once they get it. Adult actors, they really want to get in-depth and really get minute about stuff – which is awesome, which is the way it should be because God is in the details – but with Simone we rehearsed for close to two months before we started shooting. That rehearsal consisted of talking about each scene in-depth and also just spending a lot of time together and getting her comfortable doing the scenes with the other actors and with me.

Directing and [acting] at the same time is incredibly difficult, but one thing that is really convenient is I’ve already rehearsed with [the cast] extensively beforehand. So it’s not like when we show up on-set some other actor is stepping in; they’re still acting with me. We’ve already worked a lot of stuff out and I can actually direct through acting. So if it’s for coverage, I can act differently to invoke a different reaction from her. Rather than explain to her, “Intimidate him,” or give that direction, I can act differently to naturally provoke a different reaction, which is pretty awesome. If you’re on a regular film and you’re acting, you really shouldn’t be doing that if the director didn’t ask you to. But since I’m the director, I had that opportunity to direct in that way.

CM: The dialogue and the chemistry between you and David and Simone is all really natural. Was all the dialogue written before or was that part of the rehearsal process of coming up with that conversational style?

JC: I would say the dialogue is pretty close to script. Of course, if something doesn’t seem right, as long as it doesn’t change the intention [the actors] can change stuff. I’m not a stickler. It’s not Shakespeare, so I’m not going to keep them to every word. If they change it here and there or change the beginning of a sentence or whatever, it doesn’t matter. I think that [happened] in the rehearsal, but in the actual line-to-line, it’s pretty scripted.

CM: What was your shooting schedule?

JC: We only did 20 days– I would have shot it in 17 if I could have for money reasons, but it’s just impossible with a child. She’s in almost every scene. With the child labor laws, it’s basically impossible to shoot it like a regular indie film or these super efficient indie films that are shot in 18 days these days. That’s impossible, especially with a main character [being a minor], because they can only work five hours on weekdays, seven hours on weekends; they can only work until 11:30 at night and in the summer the sun goes down late. So we needed those extra days and we tried to shoot as much as we could that didn’t involve [Simone]… We would pre-block stuff and when she showed up, she was right into hair and makeup and [on] set. We’d explain some stuff to her, but we’d let her do what’s natural to her and the DP will follow and see if we can swing it and start shooting right away.

CM: When it comes to having such a lengthy rehearsal time, was that something that you prefer as an actor as well, or was it more from the director side?

JC: Both. As an actor I love rehearsal. Some people – especially in film – a lot of people don’t like it because they feel like it takes the spontaneity and the magic out because it is film as opposed to theatre where you’re doing it every day and keeping it fresh. In film, some people believe there is this magic doing it for the first time [and] you can’t capture the reality of it on the screen. Me personally, I still like rehearsing because through rehearsal you can get deeper and make discoveries. You can refine, you can adjust. Especially on an indie, you’re on such a tight schedule. It’s not a studio film where you have a day to do a scene, or half a scene sometimes. Since you have to move so fast, my style is I like to work stuff out before. When it comes to artistic conversations, the rehearsal is when you can bring that up really quickly. As a director and an actor, both are extremely helpful.

CM: How do you feel about auditions, both from the actor’s side and now that you’ve done it from the director’s side? Do you see it differently now when you are auditioning as an actor since you’ve been on the other side?

JC: Sure, yeah. I’m an auditioning actor and auditioning is just a way of life for most actors. So you learn that it’s not you. You work hard and you put your best foot forward, you do the best you can, and as an actor, you give them you. You give them what only you can give, which is your authentic performance. And if it works out it works out. On the director side, it’s not about whether someone’s good or not, it’s whether they fit the role and if they have something that can exemplify what your vision was. Auditioning for [Gook], even for this I just knew who I wanted right off the bat. Being an actor, I was like, This guy can do this, and This guy has the right qualities. For example, [Curtiss Cook, Jr., who plays] Keith, the older brother, he’s phenomenal in the film. He has a smaller part, and I’d seen him in something else. And that role, if not played well, can be a stereotypical “Angry Black Man.” I needed someone who could bring sensitivity and depth and duality to that character to be able to humanize it. And I just knew that he could do it and he could bring a really interesting element. I auditioned other actors, and they were great. They were so good, but they just weren’t what I was looking for. It’s not even that they weren’t right, it’s just they weren’t what I was looking for. So it does change the idea of what auditioning is about.

CM: When you began acting, did you always know that you’d want to create your own projects and write your own characters, or did that come about due to perhaps a lack of opportunity or interest in the types of characters that you were being offered?

JC: I always thought at some point I’d like to write because then I’m more involved in the actual construction of the characters and story. For directing, no, it never really crossed my mind and I didn’t even think that was a possibility. It’s such an all-encompassing, daunting thing that requires someone to entrust you with so much money, so I didn’t think that there’d be any opportunity for me to do that. Now, being on so many sets and doing so many indie films, you’re like, How the fuck did someone entrust this guy with that amount of money? It always perplexed me and made me think, Well, shit! I’d always do the exercise of, If I was directing this, what would I do? As an actor you make suggestions and they’re like, “No. Stay in your lane. Let me do my job, you just act. That’s your job.” It was always like, Okay, I guess that is my place. But I have opinions about how it should be done and eventually you just think, Well, I’ll just do it.

CM: Did that instruct your own directing style, in terms of being open to suggestions from your actors and not maybe treating them the way you were treated by certain directors?

JC: One hundred percent! I think great directors listen. Every director that I loved to work with was open to suggestions. Of course, they’re the captain. They can in a gentle way be like, “That’s a great suggestion, but we’re going to do it this way.” And that’s great! As an actor, that’s perfect because you’re just throwing it out there but ultimately you want the director to be the captain. The good directors are like, “That’s an interesting idea, let’s explore that,” and sometimes the scenes become better. I always think that in film it’s crazy because you watch the Oscars and all this shit, and the directors get honored and get awarded, but it’s really a community and a team effort for that to come alive. I’m only as good as the people around me, and I’m all-inclusive. So for set design, if I say, “These walls: I’m thinking of something more bland because they’re poor.” But [production designers] [Sharon] Rocky [Roggio] and Jena [Serbu] were like, “No, we need to add texture, because on-camera that’s going to read better and it’s going to bring more depth.” And I’m like, “Shit, you’re right!” And I think personally for me, the joy of directing is that it is a collaborative effort.

CM: On the other side of things, do you think your acting has changed since you started directing? Especially when you’re starring in your own work and watching dailies of your own performance, is it hard to not be overly self-aware when you get back in front of the camera?

JC: I don’t watch my performance. I don’t do playbacks. The only thing I do is I trust my DP and if he thinks we didn’t get it, he won’t direct me [but] he’ll just say, “I think we should go again.” Then I’ll make some adjustments and try to decipher what I think was lacking. I’ll tell you something really interesting, because this is [related to] SAG-AFTRA – to answer your question, it hasn’t changed my acting approach in terms of when I’m acting in someone else’s thing – when I’m acting in my own thing, yes it changes because I’m worrying about so many other things.

The most helpful thing has been taking acting classes for like 15 years and being in so many fucking acting classes and not agreeing with the teacher. I feel like a lot of acting classes in LA – I’m not saying all because there are some amazing acting teachers here – but a lot of acting teachers, their business is to direct you. So they direct you so you perform better in that scene, but they don’t necessarily give you the answers. They don’t necessarily make you self-sufficient because that’s their business. They need you to come back! They need you to always rely on them as a teacher to give the guru “right” answers. But being in acting classes for so long, you can think, No I wouldn’t do it that way, and you get into huge arguments. And eventually, you’re like, Why am I in this acting class? Most of the time you’re not even acting, you’re just watching other actors act. And when you’re sitting in those classes, you think, Okay well the teacher gave them that note but I would’ve told them to do something differently. Or, I have an idea. But obviously, in an acting class you’re not the teacher, so you keep this stuff to yourself. [Laughs] But that is incredibly helpful in working with other actors, being in an acting class and seeing how the teachers deal with them and how different actors have different quirks and you just make these mental notes of how you would talk to them.

CM: Would you have any pieces of advice for actors who are thinking about taking on directing?

JC: It’s just like acting; it’s practice. Be ambitious, but also be prepared to fail. As actors, that’s why we are in classes and that’s why we constantly train [and] we constantly fail and learn from our failures. I would say trial through fire– go out and make shorts and learn from your mistakes and be self-sufficient and know how every job works and have respect for every single position. Every single [job] is a craft just like acting, so never underestimate what people on set do. There needs to be a mutual respect and appreciation for the lighting people, the grips, even PA’s and what their function is. Being a director is not a dictatorship, you really have to respect the craft and also understand it. You can’t just show up and be like, “Hey set designers, just do your thing. This is what I’m thinking.” If you’re an actor and you have the luxury of being on set, go talk to the props department and be like, “What is it that you do and what are your inspirations when you’re preparing for a project?” That will make you a better director [and] much more knowledgeable when you’re talking to each department. But the biggest advice is, Just go do it. You learn by doing. If you don’t want to spend hundreds of thousands of dollars on an MFA directing school, I think that’s the next best way.

__

Thanks to Justin for talking with us about GOOK. Learn more about the film at the Samuel Goldwyn Films website or on Facebook and Twitter.

If you’re an independent filmmaker or know of an independent film-related topic we should write about, email blogadmin@sagindie.org for consideration.