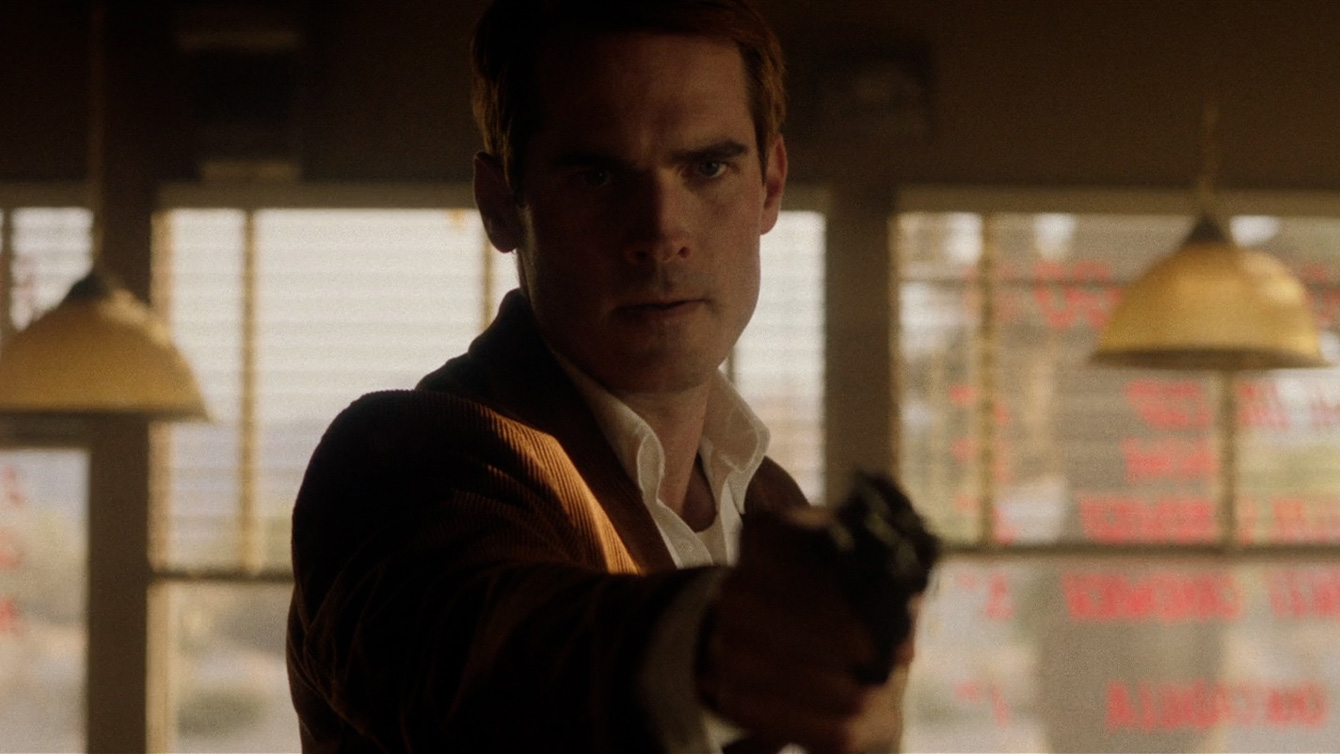

Self-taught filmmaker FRANCIS GALLUPPI has honed his skills making the most of remote locations, from a deserted highway (2019’s short High Desert Hell), to a cabin in the woods (2020’s short The Gemini Project), to — for his newest film, his feature debut — an isolated roadside diner in THE LAST STOP IN YUMA COUNTY. Galluppi’s sun-soaked crime thriller finds a traveling salesman (Jim Cummings) and a waitress (Jocelin Donahue) trapped in a hostage situation with a pair of on-the-lam bank robbers (Richard Brake and Nicholas Logan). The criminal festivities are soon joined by an array of colorful characters, played by familiar faces such as Faizon Love, Gene Jones, Robin Bartlett, Michael Abbott Jr., Sierra McCormick, Sam Huntington, and Barbara Crampton.

The Last Stop in Yuma County premiered at the 2023 Fantastic Fest before going on to international screenings in Spain (Sitges International Film Festival), Germany (Fantasy Filmfest), and Canada (Calgary Underground Film Festival). Distributor Well Go USA Entertainment will release the film in theaters and on digital platforms on May 10.

We spoke with writer/director/producer/editor Francis Galluppi about his first feature with a big cast, one location, and an unpredictable desert backdrop.

——

COLIN McCORMACK: A lot of times when I talk to filmmakers, I ask about what came first: The idea for a character or the idea for a plot. With this film, I feel like I should ask what came first: Finding the diner location or writing a script set in a diner?

FRANCIS GALLUPPI: Definitely the diner location. With my short films, I was writing based on locations we had access to because we really didn’t have any money, so I was used to that. My buddy had a house out by the Salton Sea and I went there, scouted, and was like, Okay, this is what we’re working with. I wrote a short film based on that. My buddy had a cabin up in Oregon, so I wrote something based on that. So the natural thing to do is to go find something that was period because I am always writing period pieces. I found that diner not knowing how overused that location is. I took a bunch of pictures, drew an overhead of the diner, and then started writing around that. But then after that, I was like, Oh, it’s in every TV show and commercial. But it’s okay. Unless you’re in the industry, you wouldn’t recognize it.

CM: So once you have a location and a script, what are your next steps in getting the ball rolling to make it?

FG: I had done a short film and it was playing at a festival in Cincinnati and I met somebody there who was like, “I’ll give you $50,000 for whatever you do next.” And I was like, This is crazy, I can make three features for that. Because I was making short films for $500 or $1,000. So I started writing the script and I had some experience producing, so I started producing it. I called the location, I convinced Four Aces to give us a student discount. I was going to cast off Backstage and do it that way. We ended up sending the script through a connection to Richard Brake, and he said yes. So I was like, Well, this is crazy. Maybe we can make this bigger. I optioned the script to a company that was going to make it for a lot more and it proved to be really challenging. They had a different idea of what this movie was. They were looking at it as a foreign market pre-sale kind of thing, and it was frustrating. There was a lot of gatekeeping, so once the option expired I just was like, All right, I’d rather do this thing myself.

So I started making the movie with no money. I would go to the location once a week, photo board, use Shot Designer to shot list, I started hiring [heads of departments]. I wrote letters to these indie darling actors that I loved and got really lucky casting. With the development money, I still had a casting director [David Guglielmo] on, so he helped me get these letters to them. I was in a place where I was ready to go. I had all the pieces laid out, we just needed the money. So the guy who I met at the film festival (who gave me the development money) sold his house to finance it eventually. [Laughs] Yeah, it was a truly, truly independent film. It was just myself and two other producers, good friends of mine, and we went out there and did it. It was pretty crazy.

CM: I’m curious about not only how many days the production was but how many days you were actually filming in the interior of the diner.

FG: It was a 20-day shoot. God, we were cooped in that fucking diner for at least 15 or 16 days.

CM: Without spoiling anything, there was a moment where basically every character in the movie is in the diner at once. Watching that, I was wondering how many days you had all hands on deck and how you managed to choreograph all of that coverage in a limited amount of space.

FG: It was pretty quick, I think we had to do that in a day. With special effects stuff and squibs, we didn’t have money to do multiple squibs. You got one-and-done. It was just a lot of prep, man. A lot of prep. My cinematographer [Mac Fisken] and I would go out to the location and photo board. I knew I had to commit to these oners and two-shots and I couldn’t just get a bunch of coverage because we didn’t have time. The scene that you’re referring to, yeah, there are a lot of characters in one room. It was very much [deciding] what I absolutely needed. I couldn’t just be like, “Let me get three different sizes on each character and figure it out in post.” It had to be more calculated with the time restraints.

I remember my cinematographer — who’s one of my best friends, we’ve done everything together — was like, “This is going to be a really hard day for you. There’s a lot of talent in one room.” I don’t know, it was fun [laughs]. It was really fun wrangling that whole thing and being in the middle. You have to be very, very precise in what you want because there’s so much shit happening. Every department head is off doing their own thing, they’re putting blood on the wall, and this person’s doing that, and you’ve got to take a deep breath and make sure everything’s moving accordingly.

CM: There are obvious budgetary advantages to having largely one location, but was there ever a moment where cabin fever set in and you were itching for a company move?

FG: I don’t think so. We only had 20 days so it wasn’t like we were there for that long, but it was nice to get out of there and go to where the movie ends at the field truck sequence. We shot somewhat in order. The [location] is a motel/diner/gas station out in Palmdale, [California] and we used the motel for the sheriff’s office, so we did that in one day towards the end. The last two days were out by the field for the truck sequence and it was nice to get out and leave that place, but also kind of sad.

CM: I would also think filming out in the middle of nowhere would be advantageous when you’re doing a period piece because there are fewer elements to dress.

FG: Of course. The only thing that was a real pain in the ass was to get them to remove street signs because there are modern street signs on those corners there. We eventually got the city to remove all of them. But there’s a giant warehouse in the background that we, through VFX, edited out of every single exterior wide. So now I’m like, Well if we took that out we probably could have just taken out the street signs.

CM: Were there specific benefits that you found having a fellow indie filmmaker in Jim Cummings in your cast?

FG: Jim is so professional and we share sort of the same ethos on independent filmmaking. I didn’t know Jim before this, I just had him in mind and was a fan of his work. I wrote him a letter, sent him the script, went to his house, and talked about South Park for three hours. Then he was like, “Yeah, I want to do it.” He was very, very supportive.

Like every independent film, things were going wrong. There were wind storms and rainstorms and cars weren’t working and the typical bullshit. Jim would see me with my head down and he would just come up to me and be like, “The movie’s going to be great, dude. You’re okay.” He totally gets it. We made kind of a big change in his character. I wanted a more toned-down version of what we’ve typically seen Jim in and I only had to have that conversation once. If he felt himself slipping out of character, he would immediately recognize it and be like, “Sorry, Fran. Let me do one more.” He’s very professional so it was nice to have Jim on set. He’s been through this before and done indie film and understands it. There was comfort in that for sure.

CM: Were you able to do any sort of rehearsal with your actors?

FG: A lot, actually, mainly through Zoom. I would jump on Zoom and have these one-on-ones with the actors and comb through the script. Anything that felt contrived to them, I would rewrite on the spot so that by the time we were shooting the thing, nobody was ever like, “I don’t know if I would say that.” In-person, Jim and Jocelin came during the pre-light the day before and we were able to rehearse the scene with the knife sales pitch. So it was pretty much just through Zoom, no massive rehearsal.

CM: You mentioned the VFX of the warehouse, but you also have some impressive pyrotechnics. Was this your first time navigating those action-y waters?

FG: Yeah, I had no experience. You hire the right pyrotechnic team and then you go from there. A hill that I was definitely going to die on was making sure everything was practical, from using blanks and squibs and the real explosion, to even having the Rifleman episode actually be playing on the TV and not doing that in post. I think if we were to add anything with VFX, it would stick out like a sore thumb, so all the VFX were just removal, it was never adding something to the frame. I wanted to evoke that period by using practical effects.

CM: You also have a background in music and you composed the scores for your short films. Was there ever a moment you wanted to add another responsibility on your feature debut and do the score?

FG: I did, that was the plan. The plan was to score this feature and then my son was born. I had just finished cutting it and my son was born a month early and it was right as I was going to start scoring the thing. But it was great. I’ll never attempt to score anything myself ever again after Matthew Compton. It was such a great experience, he’s awesome.

CM: How did you find him?

FG: Just through the process of having different composers demo a couple of scenes. Matt just nailed it. He really understood the tone. I’m a drummer and he’s a drummer, so we speak that same language. Every scene that he scored, he would send to me and I was just like, “Yeah, this is fucking great.” So I hope he can come back for whatever is happening next.

CM: What is happening next?

FG: I have a couple of things in the works right now. One sort of dream project that I can’t talk about, that’s next. Then a snow western that I’m really excited to make.

CM: You had enough desert and now it’s time for snow?

FG: Exactly. I always find myself writing scripts in the worst locations. God, maybe one day I’m going to write a script that takes place on some beautiful island and it can be a nice vacation.

__

Thanks to Francis for chatting with us about THE LAST STOP IN YUMA COUNTY. Learn more about the film at the Well Go USA website.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

If you’re an independent filmmaker or know of an independent film-related topic we should write about, email blogadmin@sagindie.org for consideration.